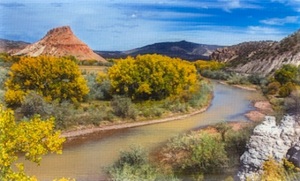

Rear view of Woodlawn Plantation, near Napoleonville, Louisiana, built in 1840. Photo taken by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1938. The house no longer exists.

My first post on Woodlawn Plantation, on November 26, begins with a front/side view of the great house taken in 1938. Since I am interested in why Woodlawn deteriorated as drastically as it did, I think that front/side view, combined with the rear view of the house shown above, will give some very good indications as to what happened.

Though certainly not looking their best, the two side wings seem to have fared quite well. You can see them clearly in the November 26 photo, though in the rear view they are seriously obscured by trees. Both wings were built of brick, stuccoed and scored to look like stone, then painted a pale dull salmon pink, like the main part of the house itself. The…

View original post 371 more words